By Cheryl Steinberg

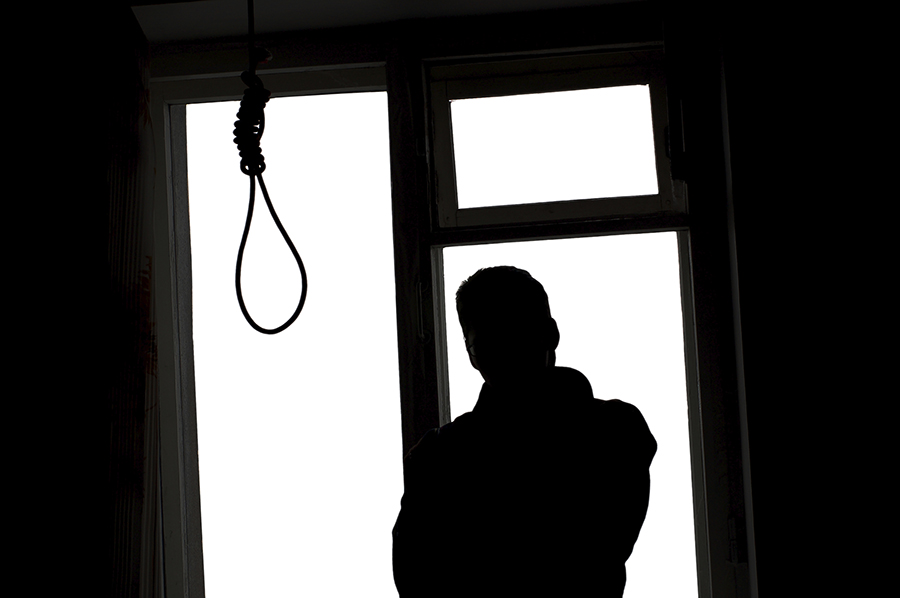

There’s a rarely-noticed and even more rarely-discussed trend happening among U.S. doctors – and it’s not something that should be swept under the rug. American doctors are struggling with addiction and depression – and even taking their own lives – at a troubling rate.

Currently, there is no official data on the phenomenon of physician suicides. Pamela Wible, a family medicine doctor in Eugene, Oregon, writes about this disturbing trend and estimates that 400 doctors kill themselves annually. Put another way, family doctors roughly see about 2,300 patients in the span of a year. That means that 400 physician deaths translate to about a million Americans who will lose their doctors to suicide each year.

Apparently, it’s something that doctors are well aware of, even if they don’t really talk about it. There’s the story of a retired surgeon recalls how his medical school professor lectured students about suicide and how to go about it. The professor had said that, if any of his students decided to kill themselves, they should do it ‘right;’ he then provided detailed instructions.

Physician Suicides are Highly Successful

Because of the stigma of depression, especially when it comes to medical professionals experiencing it, doctors ‘close ranks’ around each other and even pressure medical examiners to rule the cause of doctors’ suicide deaths as “unplanned” though they obviously are not. “Accidental overdoses?” Wible asks, skeptically. “You’ve got to be kidding me. Doctors calculate doses for a living.”

Doctors have the knowledge and training to make sure that they are successful at completing the act. They know anatomy and drugs – as well as have access to said drugs. Thus, physicians have a far higher suicide “completion” rate than the general population. An essay published in JAMA (The Journal of the American Medical Association) in 2005 stated that male doctors committed suicide at a rate 70% higher than their counterparts in other professions. And among female doctors? That rate is anywhere from 250 to 400% higher. Holy Smokes!

“Unfortunately,” says Bradley Hall, a Bridgeport, West Virginia, addiction medicine physician, “suicide is one thing doctors are pretty good at.”

The Whys: Addiction and Suicide is Rampant Among Doctors

There are a lot of theories floating around as to why so many doctors kill themselves each year. First, American physicians have to deal with the pressures of “assembly-line medicine,” daunting scheduling demands, dealing with insurance companies, keeping up with growing regulations and constantly new scientific findings and literature in their field. All of that while under constant fear of a malpractice suit. Add to that personal debt – medical school and training is expensive, after all – and doctors’ debt often totals hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Yet another aspect to consider – yet again – is the stigma surrounding depression and, of course, addiction, which is heavily tied to the trend of physician suicide. Although it’s routine for family doctors (i.e. PCPs and internists) to screen their patients for depression and anxiety, the doctors, themselves, have a different set of expectations. As Wible says, “In general, we’re in a profession that will shun you if you show weakness or suffering in any way.” She adds that, in medical school, students are taught to put aside their own emotions, even when they attend to tragic cases.

Doctors and Depression: Statistics

A study found that only 22% of medical students who demonstrated signs of depression actually sought help from a therapist and that only 42% of those who experienced suicidal ideation got help.

Instead, many doctors turn to self-medicating; after all, they have the knowledge and access to do so. About 9% of the U.S. population suffers from an alcohol- or substance-use disorder. However, that figure is between 10 to 15% among doctors.

Doctors, Substance Abuse, and Treatment Options

Physicians’ health programs (PHP) are in charge of treating doctors with substance use disorder and/or mental illness. PHPs answer to the medical boards, which have ultimate say over a doctor’s competence. Paul Earley, an addiction medicine physician and medical director of a PHP in Atlanta, admits that the current one-size-fits-all approach to alcohol and drug treatment isn’t perfect. “Are we being tougher on physicians than the general population?” Earley asks. “Yes, we are. Frankly, if you sign up to be a physician and put other people’s lives in your hands, you have a greater responsibility to the public than if you work in retail.”

But, many doctors who seek or who are referred for treatment are required to attend a pre-selected rehabilitation facility for 60 to 90 days and afterward must agree to monitoring and drug testing, which the doctors, themselves, usually have to pay for. If a doctor resists recommendations made by the PHP, they run the risk of losing their medical licenses and therefore their livelihood.

Many doctors believe the approach to addiction treatment should be tailored to the patient; the current options are too limited and are at odds with what modern medicine has shown us about treating mental health disorders and addiction.

The Takeaway

There is a massive distinction between being diagnosed with depression and being wholly incapable of performing a profession’s duties. Understandably, physicians should be screened and monitored carefully , in general, because of the nature of their work. However, when a diagnosis becomes a defining blow to one’s career and sense of self, what then?

“Acknowledging a history of mental health or substance abuse treatment triggers a more in-depth inquiry by the medical board,” wrote Dr. Robert Bright, a psychiatry professor at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Arizona. “The lack of distinction between diagnosis and impairment further stigmatizes physicians who seek care and impedes treatment.”

Depression, thoughts of suicide, and anxiety are all medical conditions that need attention and treatment. Often, these are present in individuals who also experience a substance use disorder, such as alcohol use disorder and opiate addiction, for example. Palm Partners offers dual diagnosis treatment for professionals who struggle with co-occurring conditions like these. Please call toll-free 1-800-951-6135 day or night.